Shared Compression Dictionaries promise smaller HTML responses and faster navigations.Implementing them on a real website without a CDN turned out to be a lot more educational than expected.

Shared Compression Dictionaries are one of those web platform features that make you think: "Why haven't we been doing this all along?"

So last weekend, with some rare uninterrupted time, I decided to implement Compression Dictionaries on our RUMvision.com website.

Read RUMvision's Compression Dictionaries explanation guide if you're new to the concept

The (reasonable) assumption

My initial assumption was fairly straightforward:

- Create a

dictionary.datfile - Serve it with the correct

Use-As-Dictionaryresponse header - Link to it from HTML responses using

rel=compression-dictionary - Let the platform do the rest

However, there was one important detail: our website is not running behind a CDN that compresses responses on the fly. It's a PHP-based site, served directly.

That means there is no "magic layer" that suddenly starts emitting dictionary-compressed responses for you based on some headers.

Down the PHP rabbit hole

After a brief moment of thinking "maybe this just isn't practical without a CDN", a DM conversation with Ryan Townsend convinced me to keep digging.

To my surprise, it is possible to get this working in PHP alone (with some gotchas maybe), as long as you're willing to handle the edge cases yourself.

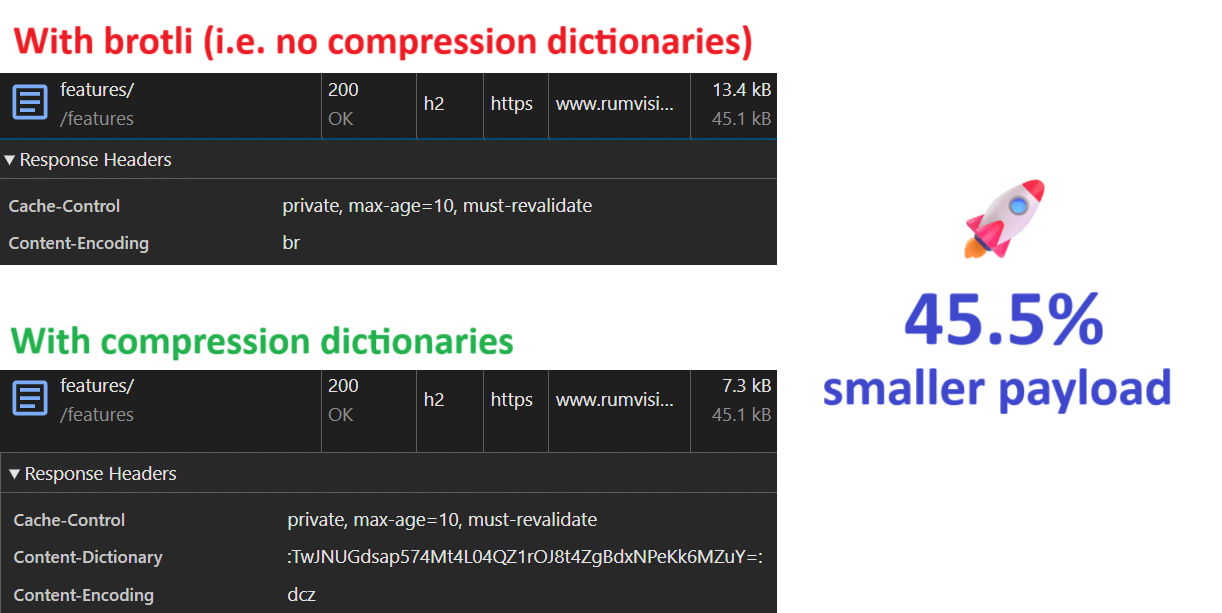

Once the first DCZ-compressed HTML responses showed up in DevTools, it felt like a breakthrough moment.

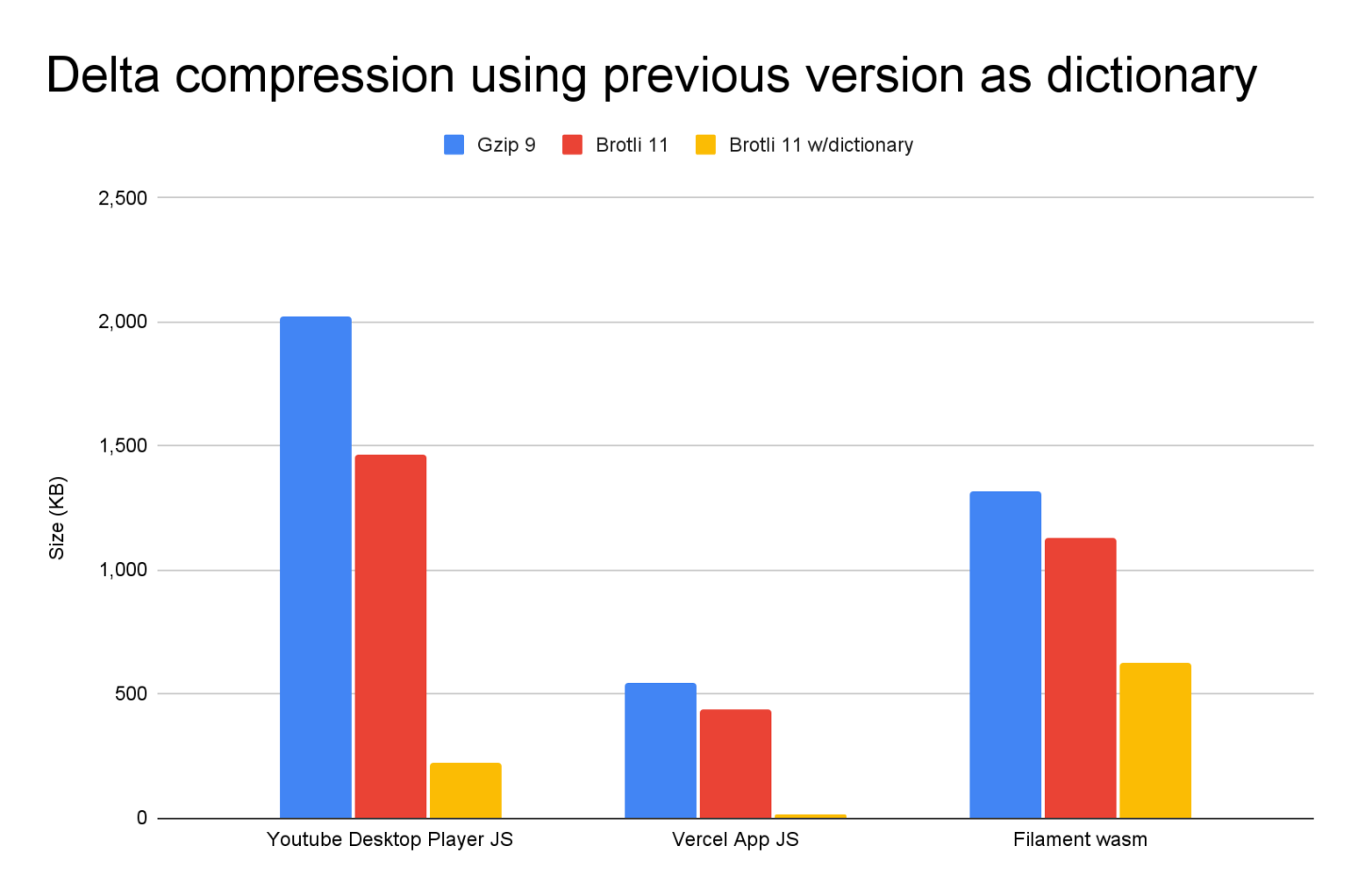

Early results were promising:

- HTML transfer size savings of ~45%

- Consistent wins compared to Brotli

- No client-side runtime cost

Not a bad start.

Why I only apply this to HTML

If you've read more about Compression Dictionaries, you may have seen examples where they're applied to CSS as well. For example, this article in the Web Performance Advent Calendar explores dictionary compression for stylesheets.

That approach can make a lot of sense in certain setups, especially when CSS is generated dynamically or frequently changes. In my case, I deliberately chose to scope this implementation to HTML only.

HTML behaves very differently from CSS

HTML is inherently dynamic. Even on fairly static websites, HTML responses tend to vary per request:

- Page content

- Navigation state

- Conditional markup

- Personalization or experiment flags

Moreover, it's typically not allowed to be cached for long durations as site owners want visitors to see the latest changes in case of updated product information or even fixed typos.

Because of these combinations, HTML keeps benefiting from compression on every navigation.

CSS or any other static text-based file, on the other hand is usually:

- Highly cacheable

- Fetched once per session (or even less)

- Served as a static file

Once CSS is cached after the first page view, dictionary compression offers no additional benefit until a next deploy.

PHP, concurrency, and server-side cost

There's also an important backend consideration.

HTML responses already go through PHP-FPM. They're rendered dynamically, so applying dictionary compression there doesn't fundamentally change the request path.

CSS and JavaScript files typically do not. They're served directly by the web server, which is exactly what you want for concurrency and scalability.

To apply dictionary compression to CSS in my setup, I would need to:

- Route CSS requests through PHP

- to apply headers and compression logic dynamically

That would mean:

- More PHP processes in use

- Lower concurrency under load

- Worse behavior during traffic spikes

A concern in my case, especially when implementing it on other sites in the future.

Scoping the solution

Given all of that, limiting Compression Dictionaries to HTML felt like the right trade-off:

- HTML: dynamic, varies per request, always goes through PHP -> good fit

- CSS: static, cached early, served directly -> diminishing returns

This keeps the implementation focused, predictable, and safe to roll out.

About generating the dictionary

There are tools that can generate compression dictionaries for you automatically, such as use-as-dictionary.com. These can be very useful when you want to train a dictionary based on a large corpus of pages.

For this first implementation, I deliberately kept things simple.

My initial dictionary.dat is essentially:

- A representative HTML document

- With the

mainsection stripped out

That keeps the shared parts: head, header, footer, navigation, repeated markup. All while excluding the most page-specific content.

It also serves another purpose: it makes it very clear that a compression dictionary is not a special binary format. It's just bytes. In this case: HTML bytes. Very simple, and very convenient when you're looking to incrementally improve your dictionary.

Don't break page navigations

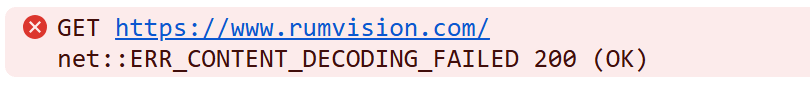

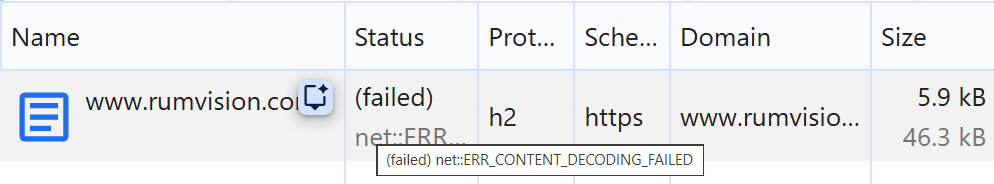

Which is what I did. And then things broke.

After updating the dictionary a few times during development, some navigations suddenly rendered.. nothing.

Chrome showed:

net::ERR_UNEXPECTED_CONTENT_DICTIONARY_HEADER

For example in the Network panel:

The response status was still 200 OK. Headers looked fine. But the browser refused to decode the HTML.

The key insight is this tha Compression Dictionaries are validated by hash, not by filename or URL.

When a browser sends the Available-Dictionary request header, it's not saying:

"I have

dictionary.dat"

It's saying:

"I have a dictionary with these exact bytes, and this is its SHA-256 hash."

If the server responds with dictionary-compressed HTML using different bytes (even if the filename is the same) the browser aborts decoding.

That's exactly what was happening:

- I updated the dictionary on the server

- Browsers still had an older version cached

- Same name, different bytes, different hash

CompressionDictionary PHP class

I wanted to make it easy for myself to re-use my implementation on similar PHP sites. So I ended up writing a class around my initial implementation.

A deliberate design choice: hash-first lookup

But I wanted to be able to deal with multiple versions while not breaking anything. One conscious decision I made early on was not to work with lookup lists or mapping tables.

Instead, I wanted the request itself to be the lookup key:

$availDict = $_SERVER['HTTP_AVAILABLE_DICTIONARY'] ?? '';

$reqHash = parseAvailableDictionaryHash($availDict);

In my script, if the browser sends a hash, that hash directly maps to a file on disk. No database lookups, no array maps, no additional indirection.

Why does this matter? Because Compression Dictionaries exist to improve frontend performance. They shouldn't meaningfully hurt backend performance because of increased backend complexity.

On a typical page request, the backend is already doing work:

- Template rendering

- Database queries

- Business logic

Adding 10-20 ms of overhead just to decide whether compression applies wasn't acceptable to me. With a hash-based file lookup, the fast path is effectively:

- Parse header

file_exists()and fetch its contents- Compress HTML

If the file is there, we use it immediately. If not, we fall back.

Never force compression

Another important rule emerged quickly: If there is no matching dictionary, do nothing.

That means:

- No overriding

Content-Encoding - No attempting to "guess" the dictionary

- No clever fallback hacks

If there's no hash match, the response simply goes out with the default encoding. In our case, Brotli.

This ensures:

- No broken navigations

- No blank pages

- No protocol violations

Debugging and observability

One lesson I learned quickly is that debugging dictionary compression is very different from debugging "normal" HTTP issues.

To make this manageable, I deliberately track why dictionary compression was (or wasn't) applied.

Examples include:

- No

Available-Dictionaryheader - Hash mismatch

- Cached dictionary hit

- Successful DCZ compression

Which is why I expose the reason in my PHP class. Which you can then log server side, or expose via Server-Timing headers.

This serves two purposes:

- Manual debugging: instantly visible in DevTools Network panel (or just the raw

Server-Timingresponse header) - RUM analysis: collected automatically by tools like RUMvision, which support Server-Timing ingestion

This made it much easier to reason about real-world behavior across different sessions and cache states.

Testing gotchas: prefetch and prerender

One small but important testing detail:

While debugging, I temporarily disabled JavaScript to avoid interference from Speculation Rules or other forms of prefetching.

This ensured I was always inspecting real navigations and raw HTML responses, not background prerenders.

Practical limitations and hosting constraints

One thing worth calling out explicitly: this implementation relies on a level of server control that you won't always have.

In my case, the website runs on our own VPS, which gives us freedom to:

- Execute system binaries such as

zstdfrom PHP - Control response headers precisely

- Inspect and manipulate binary payloads

That is not a given on all hosting setups.

On many managed hosting platforms:

- Functions like

proc_open()orexec()may be disabled - Custom binaries may not be available

- Response headers may be normalized or overridden

In those environments, implementing Compression Dictionaries at the application layer becomes much harder, or outright impossible. You may need:

- A CDN that supports dictionary compression

- A reverse proxy layer you control

- Or server-level support beyond shared hosting

This is another reason why Compression Dictionaries are not yet a universal solution. They work best when you have sufficient control over your delivery stack.

That said, the core concepts still apply. As support matures and more infrastructure layers adopt dictionary compression natively, these constraints should become less of a barrier over time.

Performance trade-offs

One important limitation of my current implementation is that dictionary compression happens by spawning a zstd process for every HTML response. While this works well and keeps the logic self-contained, it does come with a measurable server-side cost. In my case, around 7 milliseconds for stream_get_contents($pipes[1]) and 10 milliseconds for the whole process.

Process startup, piping data in and out, and waiting for compression to finish adds a few milliseconds per request. Acceptable in my case, but not free. If I wanted to push this further, there are two obvious next steps.

- avoid process startup altogether by using zstd directly inside PHP, for example via a native extension or an FFI-based binding. That would remove the fork/exec overhead entirely and turn compression into a pure in-process operation.

- introduce a small, long-lived local worker that keeps a zstd process running and accepts compression requests over a Unix socket. This keeps the application code simple while eliminating repeated process creation, and can significantly reduce CPU overhead under load.

Server side caching the $payload would be a third, but I personally didn't want to go there.

Both approaches add operational complexity and were intentionally out of scope for this first iteration. For now, the goal was correctness, safety, and learning.

Final thoughts

Is it worth it?

Yes, with caveats.

Compression Dictionaries are powerful, but they're not "plug and play" yet, especially outside of CDN-backed environments.

You need:

- Version-aware logic

- Strict correctness

- Safe fallbacks

- Good observability

But when done right, the wins are very real.

Improvements

There's always room for improvement. Or optimization of the process. For example, I'm looking to adjust my implementation to keep my latest dictionary as efficient as possible.

I could achieve this by grabbing a recent pageload and stripping the main contents to practically be left with a skeleton. I refill this skeleton with pre-defined HTML of components across different pages.

By forcing the CMS to automatically roll over to the new dictionary, all users keep benefiting from most optimal compression as the dictionary continues to be an exact match with most parts (including hashed filenames) of our HTML pages.

What's next

This post focused on the implementation journey, the sharp edges and first results.

With my PHP class, I'm looking for a high(er) traffic production site to implement this and collect RUM data. That will then end up in its own blogpost.